Stephanie Doering

A Snapshot of Image Analysis

While interviewing with UN&UP in my search for a summer internship, chief program officer Mike Sabo asked me what my favorite General Education class was in college. I responded with Intro to Astronomy, which spawned a conversation of the vastness of the universe and how neuroscience reflects such enormity at a much smaller scale. Such never-ending complexity and novelty was similarly found in the following 10 weeks as I worked on image analysis for their ongoing projects. Much like astronomy and neuroscience, I loved it.

While my thesis lab resides within the Radiology Department and I work with MRI and PET scans every day, I would in no way say I am an expert in “image analysis”. We have pre-existing analysis pipelines, scripts, and an entire processing team at our disposal. So when I was given a few videos with test tubes and asked to write a script that automatically finds the meniscuses at each frame, I was stumped. I felt under-qualified and unsure whether I’d be able to deliver what they were asking. After a few deep breaths, and about 100 Google Chrome tabs open to StackOverflow, I got to work. And to everyone’s surprise (mine especially), I was showing a fully automated script just 2 weeks later.

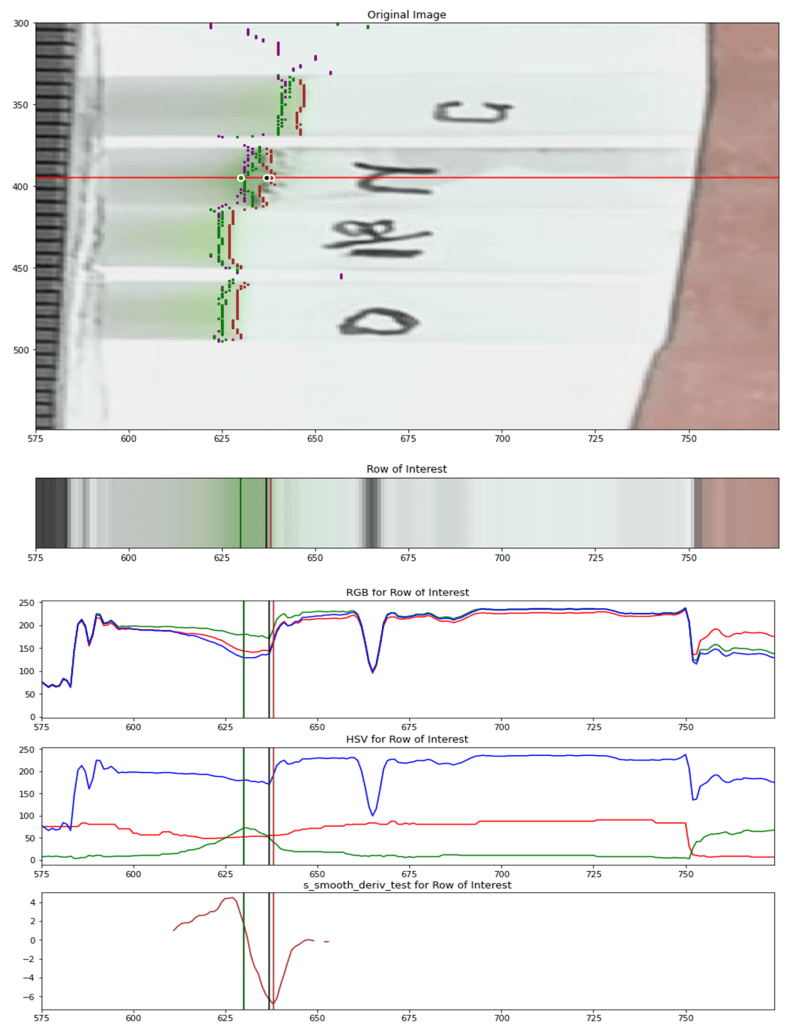

I could go into the details of how I approached this image analysis task, but I’m sure very few people are interested in how I converted the RGB images to isolate saturation then used a 5-pixel kernel smoothing function before taking the derivative to identify the lowest point as each tube’s meniscus, etc etc. So instead I’ll say, there’s no better tool at a programmer’s disposal than the internet and a little confidence. The first version of my script was not something I’d ever show to the people at UN&UP, but it was a start. Isolating each row of a photo to look at the different image components and then tweaking and editing my algorithms for finding the meniscus was part of the process. Completely throwing out those algorithms and starting fresh when I got a better idea was also part of the process. But with each new version of the script, I got closer and closer to a product that I could be proud of and gained new skills I will carry forward in my career.

Throughout the 10 weeks, I made suggestions for edits to make to the script and experimental setup, including adding a second ruler for our pixel-to-millimeter conversion factor so as to account for image distortion from the top to the bottom of the image. I also added a user interface so that the user can easily run the analysis on their desired data and would not need to edit any code in the process. While there was so much more I wanted to do as well to tweak and perfect this project’s script, I was asked to start working on a new project that they were starting since they were so happy with my results already. This is when I learned that in the start-up world, you have to be flexible and adapt. At any second, a new grant proposal will become the priority and it’ll be all hands on deck. The benefits of creating a way to analyze their data for this new project greatly outweighed the benefits of making minor, technical edits to the fully-functioning script I had already created for the original project.

Through the Pivot 314 Fellowship, I acquired a strong understanding of what it is like to work for a biotech startup. Things move quickly, so I learned to as well.